A PLANNING expert has called for the rulebook to be ripped up after a string of major developments were approved in Oxfordshire despite furious opposition.

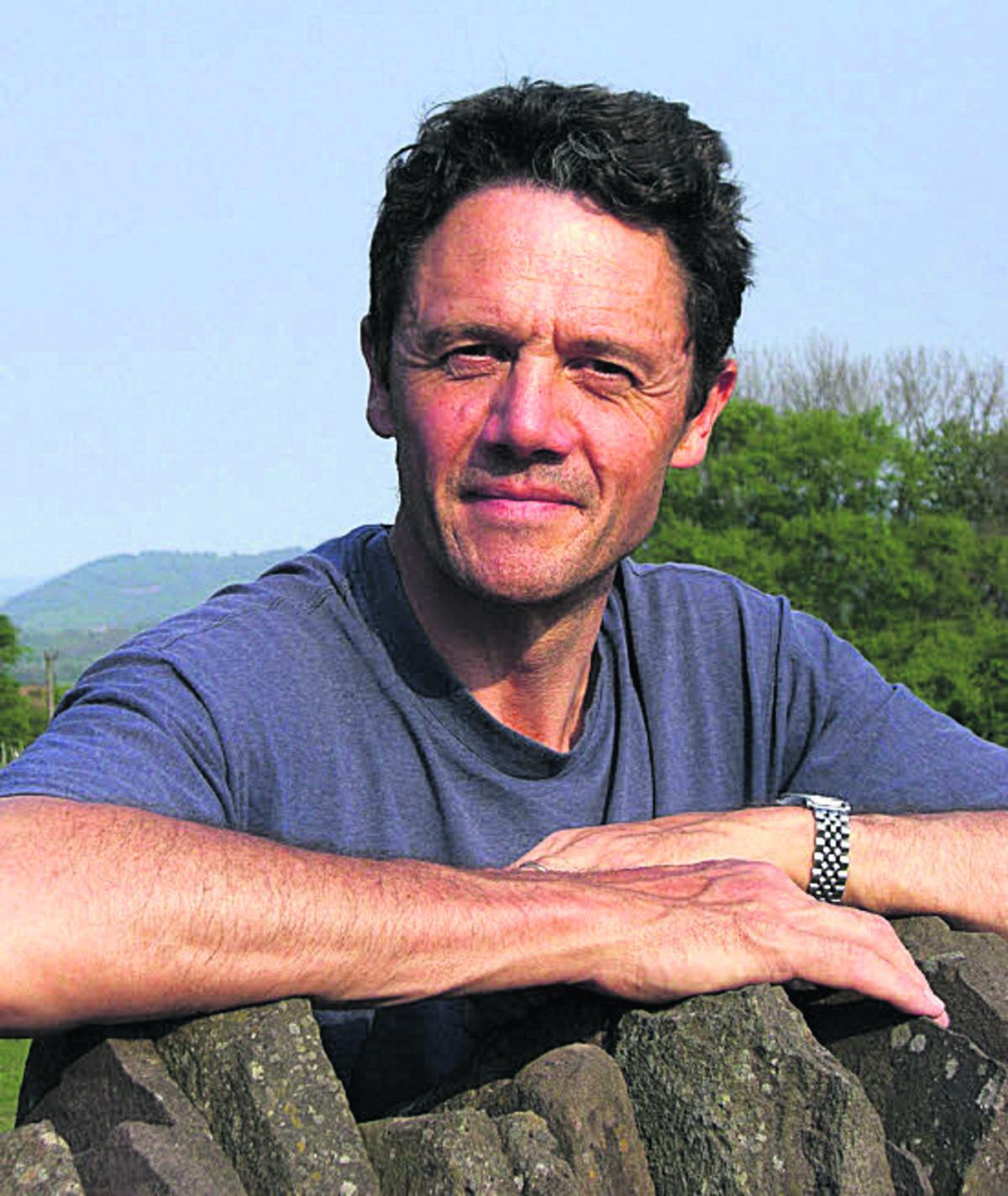

Ben Hamilton-Baillie, an expert who has advised Oxfordshire County Council on planning, says common sense is being ignored in the way the process works.

His criticisms echo the views of campaigners who say planning inspectors often overturn local decisions and overlook the feelings of local people and council chiefs.

They say this is because planning inspectors listening to appeals on schemes thrown out in the county approve plans on cold, hard legal guidelines and do not listen to what people living in an area want.

They say this has led to approvals for a free school in Cowley, a 160-home scheme in Abingdon, a wind farm in north Oxfordshire and a care home in Wantage.

Taxpayers’ cash is being wasted, critics say, as councils try to oppose plans by locking horns with high-powered lawyers of wealthy developers – only to lose out.

Mr Hamilton-Baillie is calling for a review of the planning process.

He said: “Common sense and local knowledge are lost. I am staggered by the amount of scarce public resources frittered away.”

Mr Hamilton advised Oxfordshire County Council on the potential re-design of Frideswide Square to make it pedestrian-friendly.

The urban design and movement expert was also commissioned by Oxford University in 2007 to draw up plans to show how the Parks Road-South Parks Road junction by Oxford’s Natural History Museum could be opened up as a shared space for pedestrians, cyclists and cars, although the designs were never taken forward.

He said the planning system generates the kind of responses from developers which involve “expensive long reports, which are far too complicated for councillors to understand, usually written by 21-year-old graduates.”

The system, he said, resulted in “two bodies speaking two different languages”.

There are clearly two sides in these pitched battles.

In 2010, the planning inspectorate overturned a council decision and approved a £10m plan for four wind turbines near Fritwell and Fewcott in north Oxfordshire. That cost the council £7,000 in legal fees.

Cherwell district councillor Jon O’Neill plans to urge his council’s overview and scrutiny committee to review planning policy.

He said the council was “already paying the price in terms of planning appeal costs” and called for the creation of a “stronger and more robust policy”.

Pensioner Peter Dodd also felt “let down” by the planning process.

The entire population of Abingdon, it seemed, was fighting plans for 160 homes off Drayton Road.

Vale of White Horse District Council threw out the plans, but they were approved by a planning inspector because the Vale could not offer a five-year plan for where homes could be built.

Vale council leader Matthew Barber said that the council’s hands were tied.

Mr Dodd, who lives in Virginia Way off Drayton Road with his wife Anne, said: “It is a shame that it is the inspector’s decision which overrides everyone else in town.”

Mrs Dodd called the appeal a David and Goliath battle, where the developer was able to afford a better, more expensive lawyer.

Neil Fawcett, county councillor for Abingdon South, said the appeal process “had not worked”.

He said: “Not only has it delivered a result strongly opposed by the residents, but the real flaw is that, even if we accept a need for housing, it hasn’t delivered housing in the best place in the Vale.”

When planning minister Nick Boles visited Abingdon to try to allay residents’ fears, he told them all the development that gets approved has, in the planning buzzword, to be sustainable.

He said: “It has to be economically sustainable and in terms of people being able to get about. If development is not sustainable, that is a legitimate argument against it.”

What exactly sustainable means to the man in the street seems unclear but opponents would argue that its definition is not stopping schemes they don’t want.

Mr Fawcett said he would like Parliament to look at whether the phrase “sustainable” is being interpreted in the right way.

John Sanders is county councillor for Cowley, where Oxford City Council refused planning permission for a new free school.

The Tyndale school is taking advantage of relaxed rules which mean it can open for one year without planning permission while it appeals against the decision.

Mr Sanders said there was a tension between councils that might try to please constituents, and the planning inspectorate which judges applications according to legislation.

He said the whole process should be taken away from councillors.

“There needs to be a different way of dealing with it because councillors are partisan,” he said.

“There needs to be a re-think of planning. It is not failing communities, but it is ending up with some bad decisions.”

Jane Houghton, Department for Communities and Local Government spokeswoman, said the Government had put local decision-making at the heart of the planning system and scrapped the last Government’s centrally imposed top-down development targets, which “built nothing but resentment”.

She said: “Planning and house-building always works best when it is locally led and people have a say on what happens in their area.

“That is why we’ve introduced Local Plans which will help deliver the homes, jobs and infrastructure we need.”

Health centre is caught up in row

THE Mably Way health centre was built on a field in Grove designated for healthcare.

There is room on the site either for the health centre to expand to meet the needs of a growing population or, if health care developer Ashley House gets its way, for a 60-bed private care home to be built.

In May, the Vale of White Horse District Council refused the company’s application to build the home on the grounds that it would be “prejudicial to the demonstrable future healthcare provision of the area”, and detrimental to the character of the local area.

The firm said it was going to appeal against the decision.

Bob Lewis is manager at Newbury Street Practice, one of the two surgeries operating at the health centre.

He wants the health centre to expand, with the nearby Grove health centre moving in to provide a hub for healthcare.

He said: “The care home could go anywhere but we can’t move our health centre.

“It is just unfortunate that our expansion needs to happen at the same time that this application has come in.”

The Vale council has recommended that 5,000 homes be built in Wantage and Grove in the next 15 years.

The planning inspectorate has yet to set a date for the appeal hearing.

Ashley House planning consultant Terry Gashe, of Wantage, said: “We say there is a need for what we propose.

“We will produce evidence for the planning inspector that includes census information about the aging population.”

Authorities and developers go head-to-head

THAMES Valley Police moved out of the old police station and former magistrates’ court last November, and into a new purpose-built unit at the nearby Grove industrial estate.

Churchill Retirement Living applied for planning permission to demolish the old buildings and build 45 sheltered apartments.

Vale of White Horse District Council agreed with Wantage Town Council that it would harm the town centre conservation area and refused permission.

Churchill appealed saying the scheme was “in keeping” with the area.

The Wantage and District Chamber of Commerce called the care home plan a waste of potential commercial space.

President John Naish said: “We need to provide a commercial centre and provide employment to make the town work.

“If all the thousands of new homes planned for Wantage are built, these people will need to have places to work.

“If we carry on replacing commercial sites with housing we will end up with a dormitory town.” A date has yet to be set for the appeal.

TWO groups are defying Oxford City Council to create a school and housing estate.

The Lord Nuffield social club in Temple Cowley closed in 2009.

Oxford development firm Cantay Estates bought the building and the sports grounds that surround it for just over £1.5m in 2012.

Cantay sold the building to the Tyndale Community School to open as the city’s first “free school” and then applied for planning permission to build 43 homes on the sports pitches.

Oxford City Council refused the school and the housing estate, but the groups are fighting the rulings. Tyndale free school opened yesterday thanks to the Government’s relaxed rules, which allow free schools to open in almost any building for one year without permission.

But it has also appealed against the city council’s decision.

Meanwhile, Cantay has a revised plan for 40 homes on the pitches, and says it will wait for a council decision on that before appealing against the original ruling.

Meanwhile Conservative councillors in North Oxfordshire have called for a review of wind farm policy which has cost the district council thousands in a battle over four turbines near Fritwell.

Cherwell district councillor Jon O’Neill claimed his council “does not currently have a robust policy for development of wind farms”.

Cherwell guidelines state that wind farms must be at least 800m away from the nearest homes. Settlements of more than ten homes should not have turbines in more than 90 degrees of their field of view for a distance of 5km.

Turbines should also be refused if visually intrusive or noisy, within 400m of properties and within 2km of so-called heritage assets.

The Process

Pre-planning: a developer will seek advice from the planning authority – the city or district council (such as Oxford City Council or Cherwell District Council).

Outline planning application: For a big estate, a developer will apply for general permission for the rough size of development it wishes to build.

Reserved matters: These are the fine details of an estate – what materials will be used to build the houses, the precise number and so on.

The decision: The planning authority’s planning committee, composed of elected councillors, will decide whether the development should go ahead, based on expert advice from taxpayer-funded officers and consultation with residents and parish councils.

Appeal: If the decision is refusal, the developer can appeal to the central government planning inspectorate. A hearing will be held at which a planning inspector hears evidence from both sides, usually presented by a lawyer.

Judicial review: This is a legal challenge to a planning inspector’s decision. It can only be based on a legal flaw in the evidence presented at the appeal or in the inspector’s judgement.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel