WHERE would you hide if you were a spy pursued by murderous enemies? Once you had changed your name and acquired a new identity, you could settle in “the most remote village in Oxfordshire” – Middle Ashton.

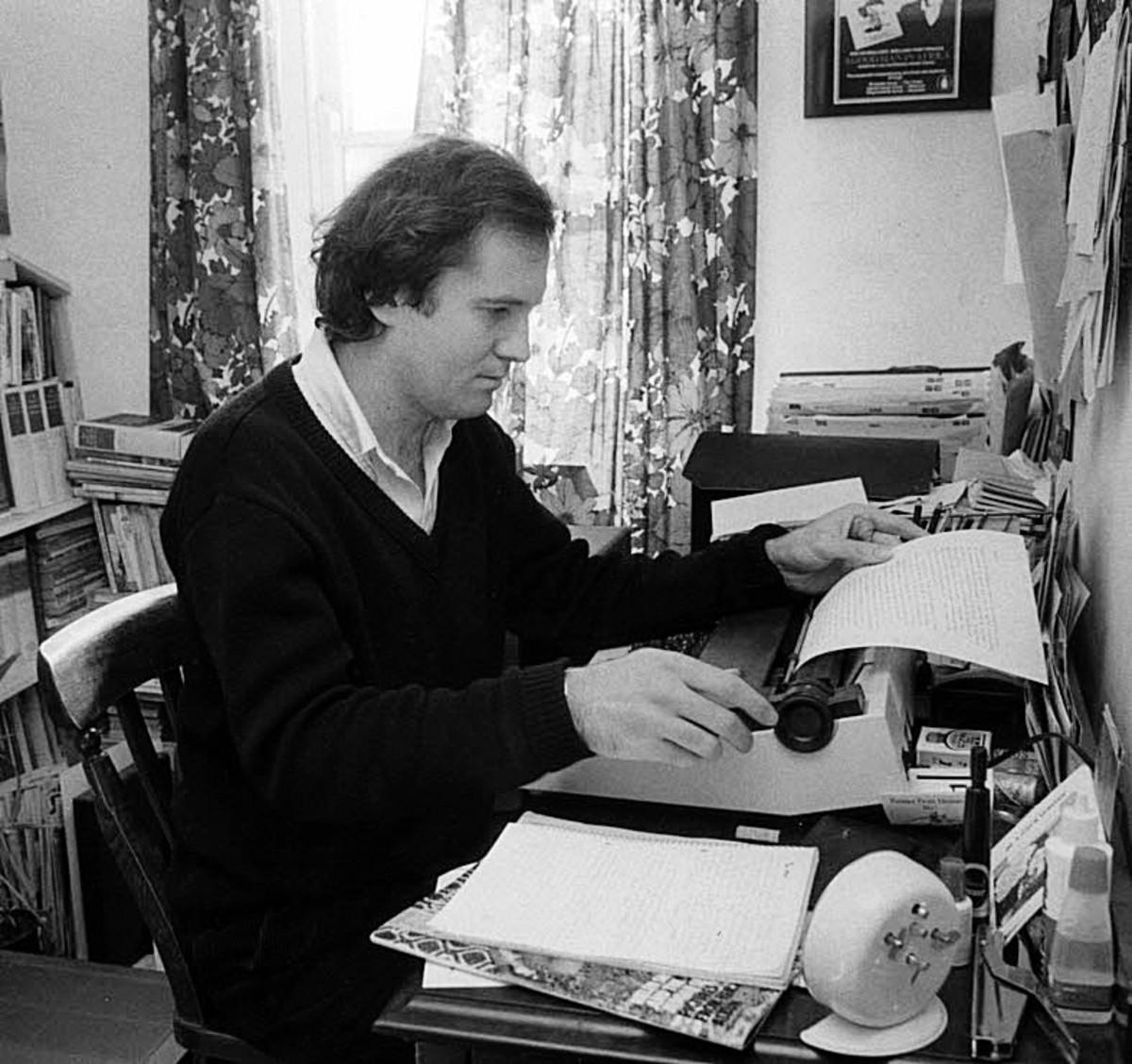

That is what the hero of William Boyd’s novel Restless did.

With interest in Boyd’s spy thrillers rekindled by his new James Bond novel, Solo, we set off in search of Middle Ashton.

We knew it was not a real place, but Chipping Norton seemed to have a fairytale quality as we got off the S3 bus in the autumn sunshine.

Boyd tells us that to get to Middle Ashton you turn off the main Oxford to Stratford-upon-Avon road at Chipping Norton, then turn off again and again, as if “following a descending scale of road types; trunk road, B-road, minor road. The tiny village is at the bottom of a narrow valley, reached by a metalled cart track through “dense and venerable beech wood”.

Boyd tries to throw his readers off the trail by mentioning “Witch Wood” so that people think his hideaway is near Wychwood Forest.

But I had prepared a dossier of clues, and I knew it was near Chippy. Like the spies in his story, we tried to throw off our ‘tail’ by walking down the hill to the church.

A wedding was in progress, so we quietly slipped between the graves and turned right to join a footpath to Over Norton.

And it was here that Boyd saw one of the views which influenced his writing, having rented a cottage here in the early 1980s, while he was a lecturer at St Hilda’s College, Oxford.

Writing the introduction to a new edition of WG Hoskins’s The Making of the English Landscape, Boyd describes the view of “an archetypal English landscape” from a bluff a few yards above Over Norton.

He could see gently undulating hills framing a long valley with the curving embankment of a disused railway, hedgerows, woods and copses, farms and homesteads. The village church was Norman, its rectory 17th century.

Beyond, he writes, lay the Rollright Stones, a legacy of England’s ancient pre-Roman past. We walked to the hill above Over Norton, but couldn’t see the stones. Perhaps he was there in the Christmas holidays, when the trees were bare. But he was right to say that you could walk, over the course of a mile or two, through centuries of England’s history – and we did.

Our group, which included a fungus expert and speleo-archaeologist (Stuart likes mushrooms, caves and industrial ruins), took a track leading west, signposted Salford, keeping straight on as the track turned from asphalt to gravel and then narrowed into a footpath.

From here we had a splendid view of Chippy’s famous landmark, Bliss Mill, part of its rich heritage as a centre of the Cotswold wool trade. The view opened out, as described by Boyd and we again tried in vain to identify the Rollright Stones on the skyline.

Stuart, meanwhile, was more interested in the old railway, which once linked Kingham and Chipping Norton with Kings Sutton on the Oxford-Banbury line.

Unfortunately we could not see any vestiges of the trackbed, since the Salford footpath goes over a tunnel, with the entrance hidden by trees.

Salford seems strangely placed – was it always set back from the main road, or was it protected by a new bypass? – until you realise that its name comes from the Salt Way leading from the Midlands, and that it was at an important crossroads with the London turnpike.

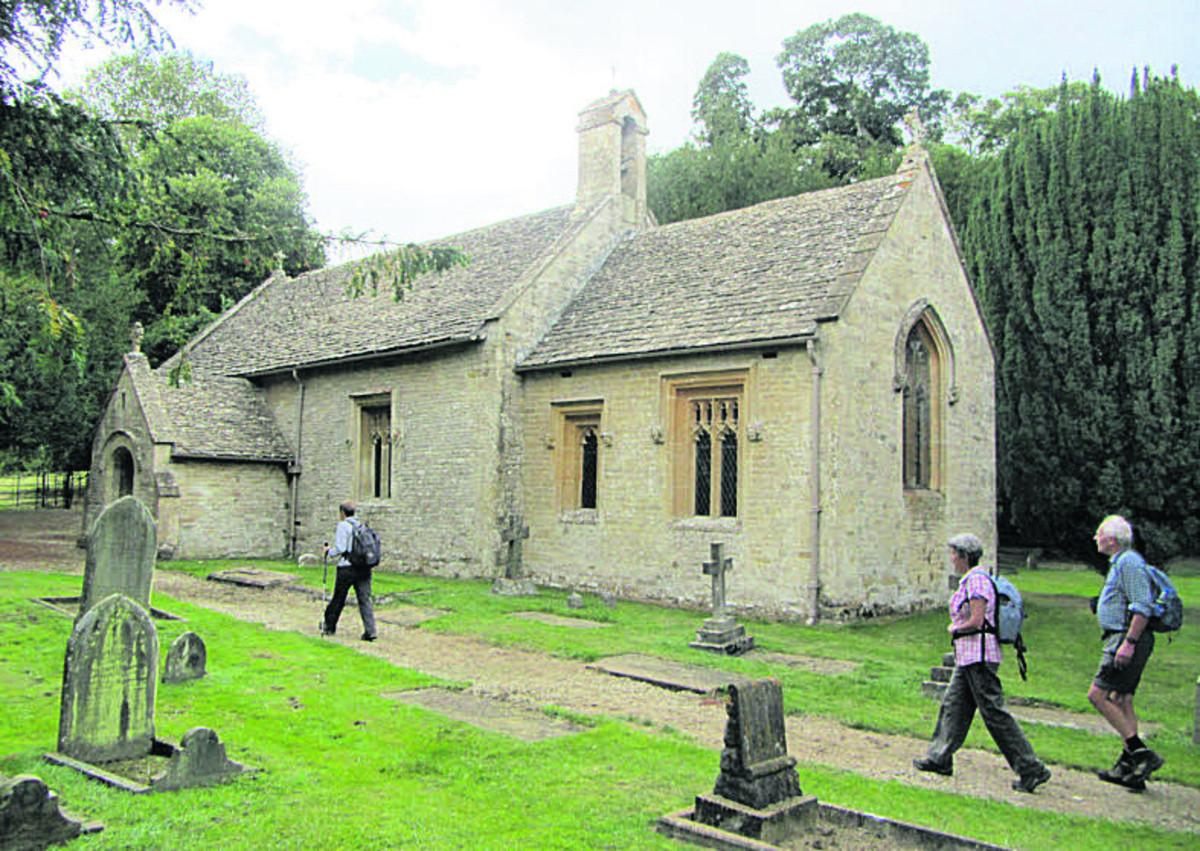

We took the path to the church – which looks like a private driveway unless you see the discreet ‘church’ sign engraved into the Cotswold stone wall – and then a footpath which joined the A44 just beyond the village.

We lost valuable time here trying to avoid walking along the main road, so I will reproduce the instructions from A Step Into The Cotswolds’ circular walk from Chipping Norton to Salford and Cornwell (but not Middle Ashton): “Do not follow the path as it bends into the church or cross the cattle grid into the field ahead. Instead turn left and follow the waymarked path at the field boundary.”

The A44 was not too bad, with a wide verge and well-trodden path, but you take your life in your hands crossing to the bridleway opposite.

In half-a-mile we were in Cornwell, where another wedding was about to start. From the grand set-up – and the trail of flowers leading from church to big house, plus the marquee in the garden – we assumed that the daughter of the Lord of the Manor was getting married.

Here was another place from a fairytale. This is not surprising, since it was part of the fantasy life of Clough Williams Ellis, creator of Portmeirion in Wales. He restored crumbling buildings, adding his own whimsical details — a bell turret, gate posts with big ball finials, curved stone brackets and chunky buttresses.

I discovered later that anyone can rent the manor for a wedding or party. But if you need to know the price, you cannot afford it. The village of 60 homes was until 2008 owned by Peter Ward, whose grave is in the churchyard, commemorated with the word ‘Wardy’.

Most of the village is protected from prying eyes by gated private roads, so it would be a good hideaway for a spy, but there is a public footpath — part of the D’Arcy Dalton Way, a 66-mile route created in 1986 to celebrate the diamond jubilee of the Oxford Fieldpath Society and named after a founding member, Colonel d'Arcy Dalton.

However, we left the D’Arcy Dalton Way to follow the road to Chastleton hill fort. The footpath down to the village gives spectacular views, and we felt it was a good spot for early humans to spy out enemies approaching from all directions.

We rejoined the road, diverting through the National Trust car park along a path with a magnificent Georgian dovecote and a view of Chastleton House. The dovecote is raised on arches, with the loft reached via a trapdoor inside — another perfect hiding place for a spy.

Like the manor house in Middle Ashton, Chastleton is Jacobean and was indeed crumbling until the National Trust took it over in 1997. There is a further clue on the website of Boyd’s publishers, Bloomsbury, with a video of him at Chastleton, describing how it inspired Middle Ashton. Because it was owned by the same increasingly impoverished family until 1991, the house remained essentially unchanged for nearly 400 years.

There was no shop or tea-room (and no sign of Middle Ashton’s grim pub, the Peace and Plenty), but fortunately the ladies of St Mary’s Church were supplying tea and cakes to visitors. The church is almost as interesting as the manor, with traces of medieval wall paintings and floor tiles. One of the stained-glass windows looked familiar — it is a copy of Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World, the painting in the chapel of Keble College, Oxford.

The last bus from Chipping Norton beckoned – we had not expected Chastleton would be so busy, nor that the walk would take so long. We vowed to return later, when we had more time.

We set off briskly up the road, which, as Boyd writes, is “sunk six feet beneath high banks with rampant hedges growing on either side, as if the traffic of ages past, like a river, had eroded the road into its own mini-valley, deeper and deeper, a foot each decade”.

Crossing the busy A436, we took the footpath down to Cornwell, then the most direct route to back Chippy, following field paths to the A44, where we were diverted by Stuart’s wish for a close look at Bliss Mill, now converted into flats.

We just had time for more tea and cakes in the Old Mill Coffee Shop before the 5.49pm bus to Oxford arrived. It wasn’t the last bus, but the later ones take half-an-hour longer and follow such a winding route that enemy spies would be easily confused.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here