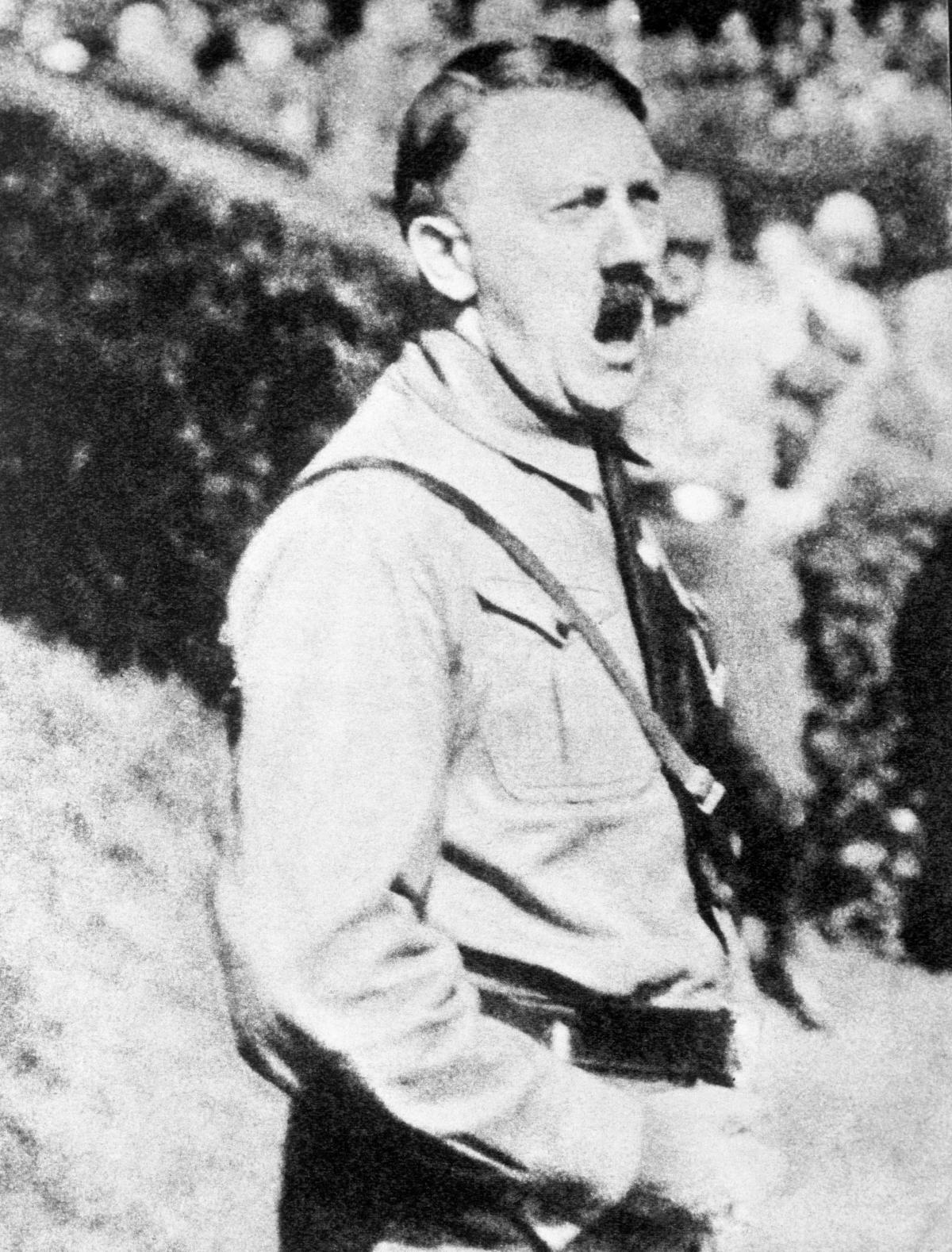

GERMAN bombers avoided attacking Oxford during the Second World War for one very good reason.

It is thought Hitler had chosen the city to be his capital once he had conquered Britain.

As we know, he never achieved his ambition. As a result, Oxford suffered little war damage, but families still faced hardships and had to make sacrifices.

In a lengthy article as peace returned, the Oxford Mail said: “The city made a very direct contribution to the war effort though, for security reasons, little has been said up to now.

“We refer, of course, to the war factories, notably those of the Morris Works and Pressed Steel Company, and there are others, too, of lesser importance.

“Oxford, of course, has been most fortunate for it escaped the death and destruction which air attacks have caused to so many cities.

“But to look back at September 1939, can you remember switching on your wireless set on that fateful Sunday morning and hearing from Mr Neville Chamberlain that we were at war with Germany?

“Two days before, on September 1, an advance guard of 18,000 London schoolchildren to be accommodated in Oxford under the official evacuation scheme reached the GWR station, and schoolmasters and billeting officers were kept extremely busy all day seeing the children were comfortably housed.

“Oxford’s mobilisation of local Territorials was almost completed by 10am on September 2, 1939, and then followed months of the ‘phoney’ war, during which Oxford’s Air Raid Precautions (ARP) exercises and training were carried out.

“A notable event in November 1939 was the opening of the Food Control Office when over 100,000 ration cards were distributed.

“Rationing began on January 8, 1940, but at that time, only butter and bacon were controlled, to be followed by sugar and meat a month later.

“One of Oxford’s most historic buildings, the Clarendon Hotel in Cornmarket Street, famous as a coaching inn and known to generations of Oxonians, was closed down at the end of 1939 and subsequently taken over by the Americans as a Red Cross centre.

“In May 1940, with disaster threatening, came the call for volunteers to meet the threat of invasion, and the Local Defence Volunteers (later known as the Home Guard) came into being.

“Oxford’s response was one of which the city could be proud, and soon companies were functioning in all parts of the city.

“In those sunny but terrible months of 1940, Oxford saw the men of Dunkirk - thousands of them - quartered at Port Meadow where they were sorted out and gradually posted to their depots and re-equipped for the battles that lay ahead.”

During the war, people were frequently encouraged to contribute money towards National Savings Weeks and similar campaigns, and invariably Oxford beat its targets.

A drive for scrap metal began in the city and after college and church railings had been taken, residents were asked to forfeit those in front of their houses.

With many men abroad fighting, the first bus conductresses and women bus drivers made their appearances in the city.

The Oxford Mail article continued: “Then came the blitz on London and the Midlands and night after night, Oxford’s Civil Defence was on duty while planes droned overhead on their way to the Midlands and the North.

“Although the crump of bombs could be heard in the distance, Oxford escaped the attention of the Luftwaffe, except for one or two minor incidents which did not result in casualties.

“London was undergoing a terrible nightly bombing which lasted for months, and large numbers of evacuees, some of them with nothing more than the clothes they were wearing, came to Oxford, providing a tremendous problem for the local authority.

“The Majestic cinema in Botley Road was turned into a reception centre and here, large numbers lived for many weeks.

“The city which was also housing several branches of Government departments, was soon badly overcrowded.

“Throughout the grim winter of 1940-1, Oxford fire service was frequently called upon to help the hard-worked firemen of London, Bristol, Exeter, Coventry, Birmingham and other places.”

In January 1941, all men between 18 and 60 were called to fire watch, outside working hours, for 48 hours a month. Women were later drawn into the rotas.

At that time, Oxford’s chief billeting officer, Stewart Swift, reported that 10,000 men, women and children had been evacuated to Oxford and that many houses were overcrowded.

The problem of feeding workers was tackled by opening municipal restaurants, one in the Assembly Room at Oxford Town Hall.

Families were encouraged to spend holidays at home and avoid using the overstretched transport system.

With the U-boat menace to Britain’s petrol supplies, road transport had to be restricted. Oxford’s bus service was cut, the last services leaving the city centre at 9pm. Gas-driven buses, known as Chestnut Roasters, were used to save petrol.

When America joined the war, troops in ever-increasing numbers began to pour across the Atlantic and the American uniform was soon a familiar sight in Oxford.

Not only was the city a favourite place for Americans on leave, there were large camps in the neighbourhood. The Churchill Hospital became an American military hospital.

In January 1943, Exercise Carfax was held in Oxford, a large-scale, one-and-a-half day operation involving Civil Defence personnel, Home Guard and troops to test the city’s response to a possible invasion. All shops, cinemas and theatres were closed and everyone was told to stay indoors.

Another feature of the war was the queue. The Mail report added: “Oxford became a city of queues - for cigarettes, cakes, fish, tomatoes, oranges, at restaurants and cinemas and for buses.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article