The casualties of war extend far beyond the terrible loss of human life. During the First World War, thousands of pigeons carried vital messages over long distances. Dogs detected mines and dug out victims of bomb blasts, while millions of horses, donkeys and mules carried supplies and ammunition or charged into battle in the Allied cavalry.

Eight million horses perished in appalling conditions. A dramatic memorial in London, sculpted from stone and brass by artist David Backhouse, pays tribute to the fallen creatures, great and small. Author Michael Morpurgo expressed his debt of gratitude in the 1982 children’s novel War Horse, which has been adapted into a breathtaking stage production. Now, Steven Spielberg directs this handsome Oscar-tipped film version of Morpurgo’s heart-rending tale from a script by Richard Curtis and Lee Hall.

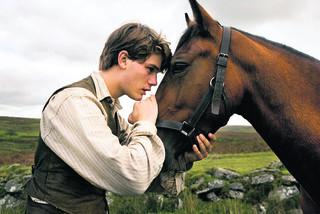

Alcohol-soaked farmer Ted Narracott (Peter Mullan) pays over the odds for a foal called Joey to spite landlord Lyons (David Thewlis) when he is supposed to be buying a plough horse. Long-suffering wife Rose (Emily Watson) despairs, wondering how they will pay the rent, while son Albert (Jeremy Irvine) promises to train the animal to work the fields.

When Europe goes to war, Ted sells Joey to Captain Nicholls (Tom Hiddleston), who promises to take good care of the mount. Albert subsequently learns of tragedy on the battlefield and enlists in the army with best friend Andrew (Matt Milne) to track down Joey and return the horse to the farm.

Meanwhile, behind enemy lines, Joey is captured by the Germans and embarks on a momentous journey in the company of a young soldier called Gunther (David Kross), a French girl (Celine Buckens) and her grandfather (Niels Arestrup).

War Horse is a deeply moving and sweeping drama that harnesses Spielberg’s virtuosity behind the camera. He conjures breathtaking images, such as the deaths of two characters by firing squad which are hidden from view at the crucial moment by the tilting sail of a windmill.

Scenes in the trenches recall the pyrotechnic-laden hell of Saving Private Ryan and a pivotal scene of Joey ensnared in barbed wire in no man’s land during the Second Battle of The Somme is horrifying. Irvine is an endearing and steadfast hero, willing to die for his beloved horse, and the supporting cast embraces the script’s earthy humour and sentimentality. Invariably, the four-legged stars canter away with our affections, embodying the millions of noble beasts which gave their lives in war.

Michael Fassbender delivers a fearless, emotionally raw performance as a sex addict wrestling with his myriad demons in Shame, artist-turned-director Steve McQueen’s follow-up to the critically feted Hunger. Brandon (Fassbender) is a handsome thirty-something office worker who is never short of bedfellows, including one of the secretaries (Nicole Beharie). Anonymous pick-ups temporarily sate his cravings for physical pleasure but at night, he hungrily scours adult sites on the Internet. Brandon’s routine of soulless couplings and seedy hook-ups is thrown into disarray by the arrival of his needy, younger sibling, Sissy (Carey Mulligan), who is carving out a career as a singer.

Shame pulls no punches in its depiction of Brandon’s base desires. The camera doesn’t spare blushes and the ensemble cast place their trust entirely in McQueen as he exposes the hollowness and despair beneath each instance of supposed pleasure.

Fassbender meets the challenge magnificently, portraying his office drone as an empty husk, miserably alone in a city that never sleeps. Such is the ferocity of his portrayal, he should be a major contender for an Oscar. Mulligan is equally mesmerising, nabbing the film’s best moment when Sissy sings in a bar and the camera lingers on her face as she sings a heartbreaking rendition of New York, New York. Her fragile voice almost breaks and we can’t tear our eyes from the screen.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article