AMONG the mixture of old and new houses straggling along the main road through Ascott-under-Wychwood, one building stands apart.

The Tiddy Hall, built in 1912 as a reading room for villagers, is still the hub of community life just over 100 years later, and as such is a living monument to its original benfactor, Reginald John Elliott Tiddy.

Last year, a blue plaque was unveiled, ensuring a permanent reminder of the man who did so much for this small rural community in the years before the First World War.

Tragically, Tiddy himself was a casualty of the war, dying on the battlefields of the Somme in 1916, aged just 36.

But in Ascott-under-Wychwood he is more local hero than war hero; a self-effacing, generous man who became a leading figure in local life.

His research into folk plays, song and dance led to a revival of mummers’ plays in the village, along with the formation of a morris dancing side.

His work is of national importance too, with his original research still forming the basis of ongoing research today.

He was born in Margate, Kent, on March 19, 1880, to William Elliott Tiddy, an academic and schoolmaster, and Ellen Willett. His mother came from a family of Oxfordshire farmers, so Reggie (as he was always known) and his brother spent many happy holidays staying with relations and exploring the local countryside.

His early education was at the Albion House School in Margate, which his father co-owned, but in 1893 he won a scholarship to Tonbridge School, where he became head boy in 1897.

A fellow pupil was the novelist EM Forster, and Tiddy later appeared in Howard’s End, thinly disguised as Tibby, the brother of the Schlegel sisters.

He came up to Oxford on a scholarship, graduating from University College with first class honours in both classics and greats, and went on to become classics fellow at the college in 1902 and Trinity three years later.

At the time, English literature was fast emerging as a new academic discipline and, despite the widespread contempt for the subject in the university, Tiddy’s love for Anglo-Saxon and early English inspired him to change direction.

He was one of the early lecturers at the School of English and he combined his teaching with meticulous research into the plays and song texts of rural folklore.

Tiddy’s main concern was to resurrect and preserve for posterity mummers’ plays that had once been a popular part of Oxfordshire village life but were in danger of fading into obscurity.

His move to Ascott-under-Wychwood in around 1909 gave him the perfect opportunity to get first-hand experience of the Oxfordshire folk dancing tradition.

He quickly integrated into the village community, talking to residents about their memories of music and dance in the village, and eventually using the information gathered to revive its morris dancing side.

His most significant achievement, though, was to finance the building of a village hall, which became a popular venue for a variety of local events and activities – including, of course, folk dancing and singing.

It also allowed him to pursue his ambition of making education and healthcare more widely available and generally improve life for farm labourers.

Before long, the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA) was holding classes at the hall, while Mrs Furniss – wife of Henry Sanderson Furniss, later Lord Sanderson and an early supporter of the WEA – was running school clinics for the children of those unable to afford doctors’ fees.

In his Memories of Sixty Years, Lord Sanderson recalled the impact of the new hall on the community: “There was folk dancing out of doors in the summer, and weekly dances took place in the hall throughout the winter. It has undoubtedly been a great resource and recreation to the people.”

Lord Sanderson was also impressed with the way the hall brought together people from all walks of life, commenting that it had managed to “break down the aloofness and lack of fellowship which is so common in village life”.

Tiddy was also passionate about promoting higher education for all, at a time when university places were virtually unattainable by the working classes.

The recently-founded Ruskin College, with its mission to provide educational opportunities for the disadvantaged, was a cause close to his heart, and his financial support for the college in its early years undoubtedly helped enormously.

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 ended Tiddy’s rural idyll. Although a pacifist by nature, he felt it his duty to fight, and he enlisted in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, becoming a lieutenant with the regiment’s 2nd/4th Territorial Army battalion in 1915.

With asthma and poor eyesight it was a wonder he passed a medical board, and in fact it took several attempts.

Tiddy’s war was quickly over; he was posted to the Somme in May 1916 and killed by a stray shell on August 10 while searching for wounded comrades.

Perhaps the final tragedy is that he was buried in the Laventie Military Cemetery at La Gorgue Nord in France, rather than being laid to rest in the village that had been his home for the last few years of his life, and where he had become such a well-loved and influential member of the local community.

But the Tiddy Hall still thrives, and is probably a far more glorious epitaph than any headstone could be.

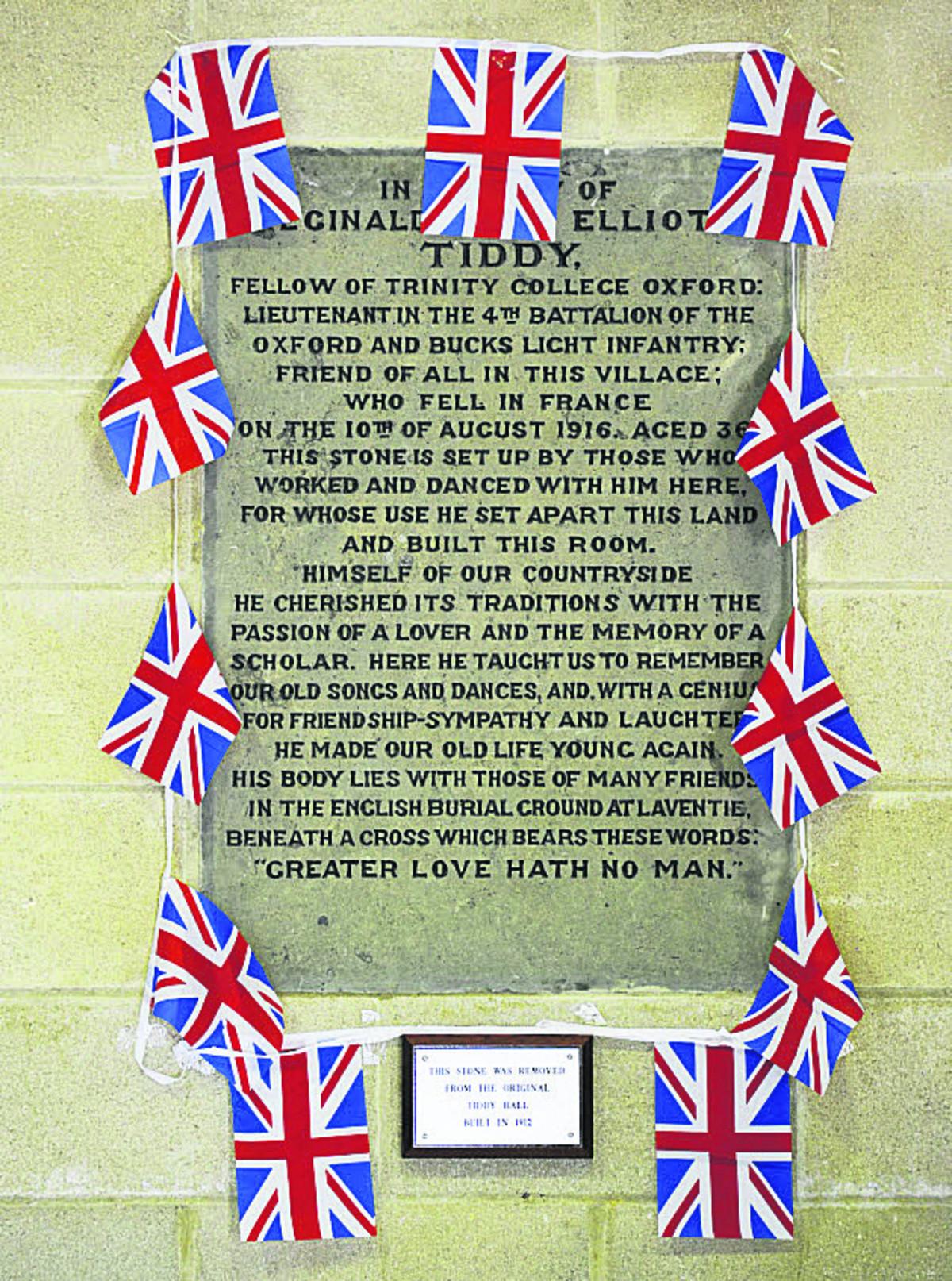

A portrait and memorial plaque inside the hall are constant reminders of Tiddy's courage and generosity, while the blue plaque outside is testament to the affection that people still hold for him nearly 100 years after his death.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here