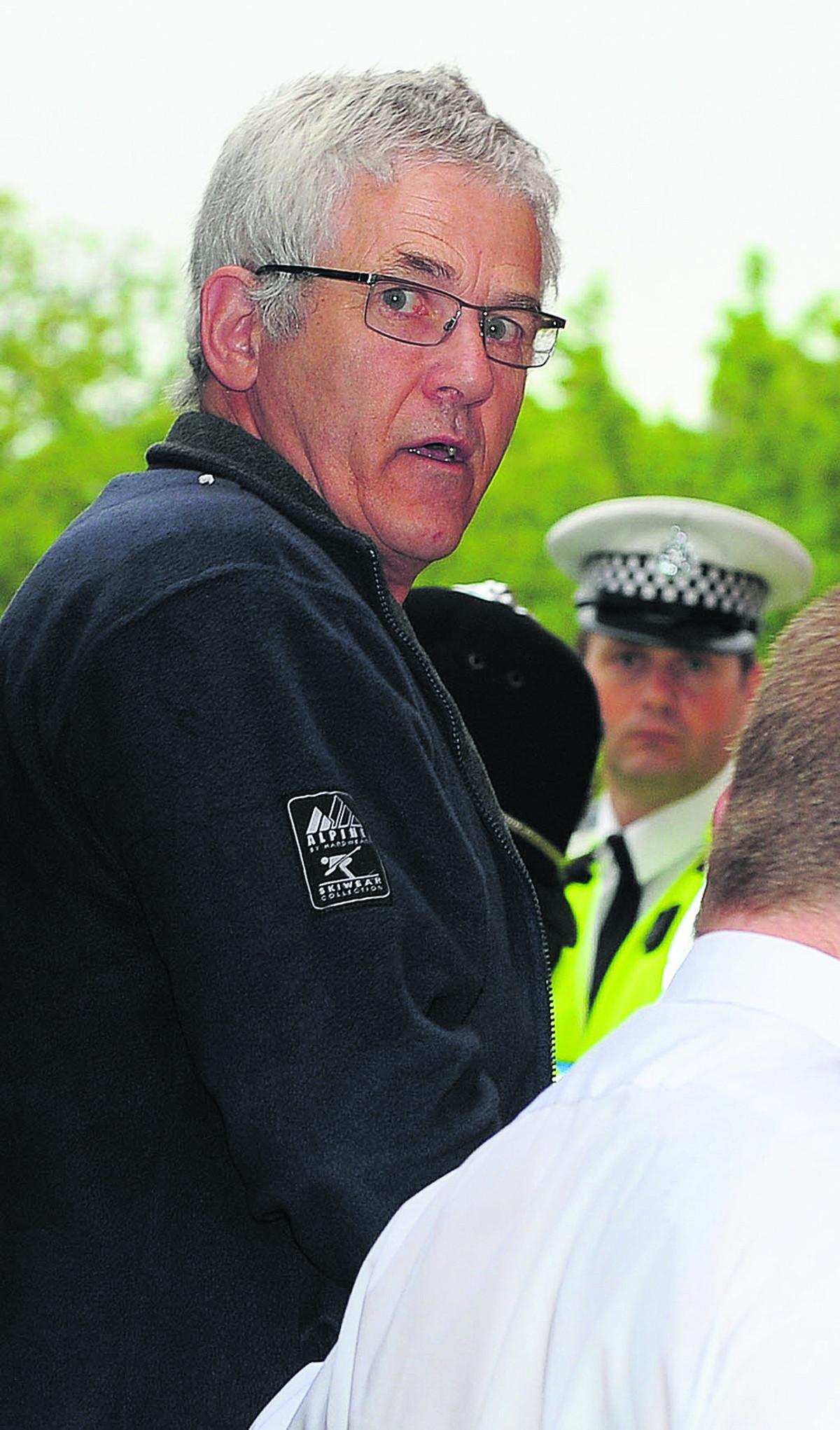

THE detective who was to finally bring to justice the killer of the Witney couple Peter and Gwenda Dixon, recalls turning to a prominent criminal psychologist, who had worked with some of the most dangerous criminals in British jails.

Det Chief Supt Steve Wilkins was anxious to hear Dr Adrian West’s view on how best to approach John Cooper.

“As we were finishing for the day I asked Dr West a simple question: ‘Adrian, how would you describe Cooper as an offender?’

“He thought for a few seconds then replied: ‘There are two people who I have come across in my professional career, who if I awoke in the middle of the night to find them in my bedroom I know I would have to kill them to survive – one is Donald Neilson, the so-called Black Panther, the other is John William Cooper’.”

Now retired after a 33-year police career, Mr Wilkins is based in Geneva, investigating the illicit tobacco trade in Western Europe.

But before leaving for Switzerland he revisited the case that he is destined always to be remembered for in a new book, The Pembrokeshire Murders: Catching The Bullseye Killer, co-written with ITV Wales News presenter Jonathan Hill.

Most people know the story of how the Witney couple were shot on a camping holiday in 1989, with their bodies found 600 yards from the caravan site where they were staying, between the coastal path and the edge of a cliff.

It was to take 8,001 days for the police to finally bring Cooper to justice, with the gunman jailed for life with no chance of parole in 2011.

The investigation would involve the police producing 30,707 documents and conducting 1,603 interviews. Operation Ottawa, as the investigation was called, received the Association of Chief Police Officers’ Homicide Working Group award for best investigation, with it being proclaimed “one of the finest investigations in British policing history”.

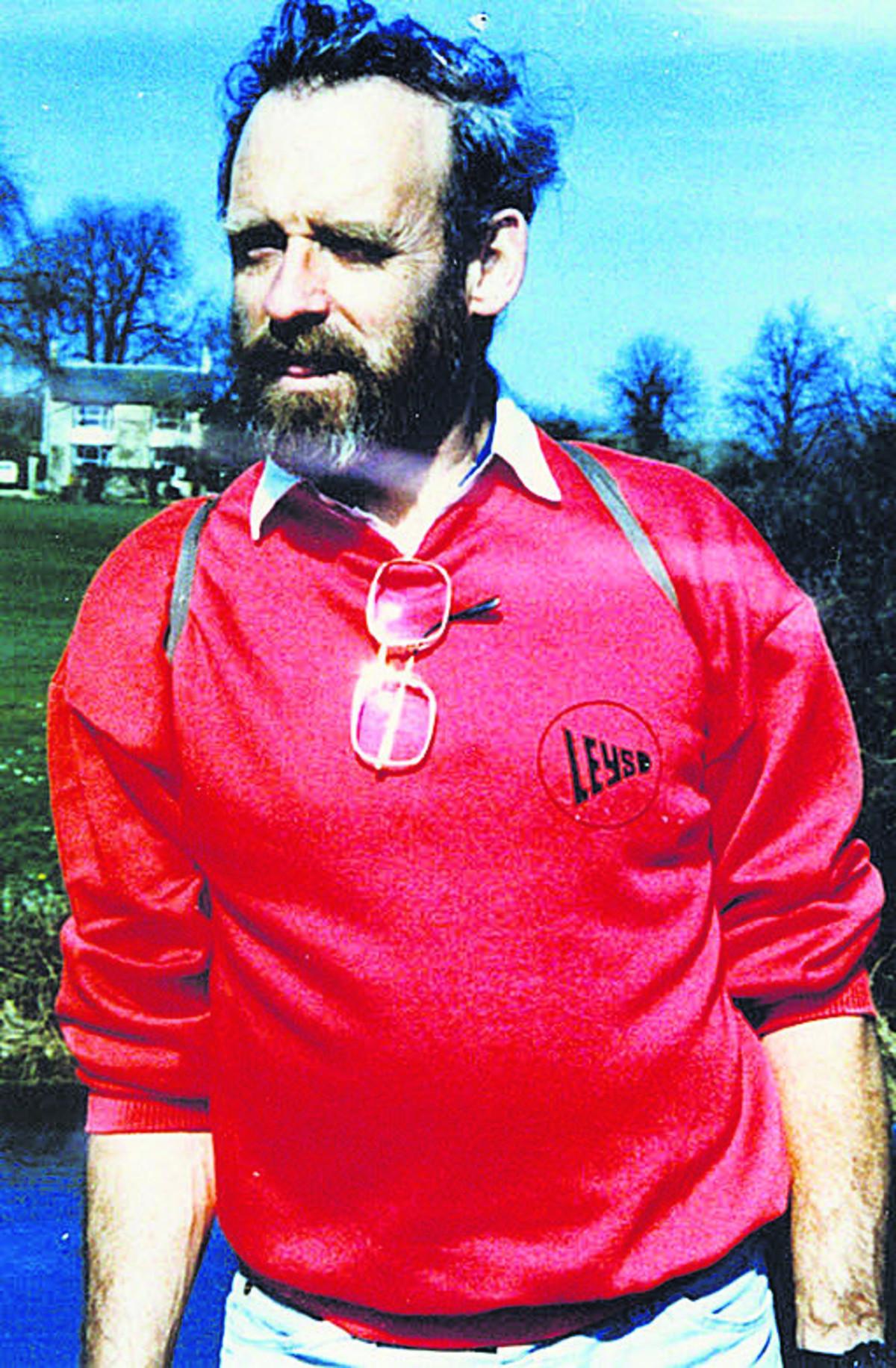

It was certainly to prove one of the most complex, with Cooper also found guilty of the 1985 murder of brother and sister Richard and Helen Thomas, who were shot dead in their Welsh farmhouse. He was also convicted of separate charges of rape, sexual assault and attempted robbery.

Long after the successful prosecution, however, the officers involved would talk of the ‘Curse of Cooper’.

“My team had great difficulty readjusting to normal policing duties following the intensity of the investigation,” Mr Wilkins remembers. “The case had consumed so much of our lives. I lived and breathed it over six years.

“Within a very short space of time two of my senior management team would seek help for post-traumatic stress. Within a month of the end of the case, my wife told me that our marriage was over. I was so wrapped up in the case that I didn’t see it coming.

“It seemed Cooper was still wrecking lives from inside his cell.”

As well as being able to give a detailed account of the investigation, he pays tribute in the book to the families of the victims, including Tim and Julie, the children of Peter and Gwenda Dixon.

Peter Dixon had been shot three times with his hands tied behind him and Gwenda twice with a sawn-off shotgun fired at close range. The execution-style killing and the discovery of an IRA arms cache near the scene led to initial speculation that they were victims of terrorists.

When Mr Wilkins was transferred from Cheshire in 1992 to Dyfed-Powys Police – a force with the fewest officers and the largest geographical area in England and Wales – it seemed no one wanted to talk about the unsolved murders.

“North Pembrokeshire was plagued with a large number of house burglaries and armed robberies where lone females were attacked in their homes by a single, violent offender,” said the retired detective.

In 1996, there were two particularly violent attacks, the first involving five children, who were threatened at gunpoint, with one of the girls raped in a field near the scene of the double murders.

During a second attack, the offender fled after an alarm was activated. As he did so, he abandoned items of clothing and a shotgun.

Cooper was arrested and given a 16-year sentence.

While Cooper was a suspect for the Dixons' murders, Mr Wilkins’s decision to undertake a forensic review of all undetected serious crime was to change everything.

“I remember being told that there was unlikely to be any significant advance in forensic science for five years, particularly in relation to DNA, so there was no logical reason to delay a review.”

Material and exhibits from the offences were recovered from storage for re-examination, with much of the testing carried out at forensic laboratories in Culham. But in the background there was a ticking clock: the realisation that Cooper would soon be released, with the possibility that he would kill again.

It was to be almost three years before Mr Wilkins had his first forensic break, when blood belonging to Peter Dixon was found on a pair of shorts recovered from Cooper.

More quickly followed, including strong fibre links and bloodstains on the barrel of a shotgun used by Cooper during the robberies. This was the weapon with which the Dixons were killed.

Then there was the discovery that Cooper had been on the ITV 1980s gameshow Bullseye, a month to the day before he killed the Dixons.

His co-author Mr Hill, who had been reporting on the case for years, was to play a key role in acquiring the tape of Cooper’s appearance on the show from studios in Leeds.

Mr Hill said: “The police were delighted, because it meant that they had moving footage of Cooper at the time of the murders.

“They already had an artist’s impression of a man seen using Peter Dixon’s cashcard after the killing. When we compared the images, there was a compelling match.”

The book offers an insight into the care taken by the detectives to trap a cold and calculating killer during hours of interviews.

Years earlier, when Cooper was linked to dozens of burglaries and robbery (he was later charged with 34 offences), he refused to answer questions about the murders, with the interview lasting just 13 minutes. The key, Mr Wilkins decided, was to get him talking in the interview room, and keep him talking.

“We discussed our approach for months. I wanted Cooper to have a free, unchallenged introduction and get him speaking about his life, interests, business ventures and family life.”

Yet for all this effort, Mr Wilkins remained uncertain of the trial outcome right until the jury at Swansea Crown Court returned with a guilty verdict to all charges, on May 26, 2011.

The words delivered outside the front door of the court room after the verdict by Julie Dixon are included to show that, for all the science and forensic reviews, the story is ultimately a tragedy of two families.

“To many Peter and Gwenda are just another two faces that happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. But to our family they are irreplaceable. Peter and Gwenda were loving, gentle and loved people,” she told the waiting world.

A dark shadow over Pembrokeshire for a quarter of a century had been lifted.

For Mr Wilkins, the book amounted to “a kind of therapeutic debriefing”, while his readers will learn something of the man Peter and Gwenda Dixon encountered on the walk at the end of their holiday, undertaken to allow their tent to dry before the drive back to Oxfordshire.

“To me the fact he kept mementoes of his offending gives us an insight into this controlling, evil man,” concludes Mr Wilkins.

“He thrived on control. When he stole keys it made victims feel that he could return in the future to terrorise them. Some of the items he stole were worthless, like the shorts he stole from Gwenda Dixon.

“Every time he wore them he was reminded of the moment in time when he held their lives in his hand.

“I have often been asked, why did Cooper do what he did? My response is simple. I believe some people are born evil and John William Cooper is one of them.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here